第3展示室

今は東京の地、江戸に幕府が置かれた時代、16世紀末~19世紀半ばの様子を展示しています。日本と外国との交流、都市江戸の社会と文化、旅行と物の流通、村の様子などについて紹介します。

①国際社会のなかの近世日本

近世日本は、「鎖国」をしていたと思われがちですが、東アジアのなかで孤立していたわけではありません。中国との正式な外交関係はありませんでしたが、長崎でオランダとともに通商関係をもち(長崎口)、朝鮮・琉球とはそれぞれ対馬藩・薩摩藩を介して外交関係をもち(対馬口・薩摩口)、アイヌの人びととは松前藩を介して通商関係をもっており(松前口)、この四つの出入り口で、人やものや情報が行き来し、国際社会に開かれていました。展示では、四つの出入り口をそれぞれとりあげて、具体的な交流の様子をみていきます。

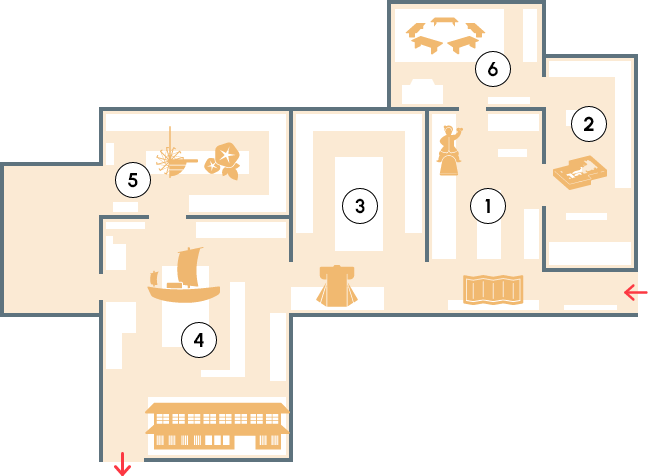

入口からの展示場風景

朝鮮通信使や琉球国王の使節が江戸に行くときの映像が見られます。

唐蘭館図絵巻(複製、原品:長崎歴史文化博物館)

当時日本に来たオランダ人などとの交流を描いた絵巻です。

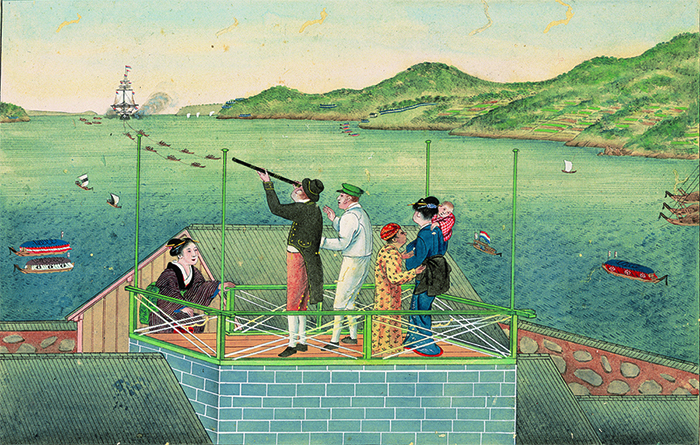

②絵図・地図にみる近世

近世日本で作られた世界図や日本図をみると、当時の人々が世界や国土をどのようにとらえていたかを知ることができます。観念や想像力が顕著なもの、伝統的な知識が重視されたもの、現地調査や実測によって知識や形態の正確さが追究されたものなど、そのとらえ方は一つではありません。近世日本では、このような多様なとらえ方が併存していました。しかし、実態に即した認識がしだいに広く浸透していき、やがて来る近代を準備することになります。 展示室では、各種の世界図や日本図を実際に並べ、また大型タッチパネルも用意して、地図の相互比較によって、世界観や国土観の変遷を考えられるようにしました。また、初めて実測によって作られた伊能忠敬の日本図を展示し、その作製過程にも注目します。そのほか、江戸幕府の作った巨大な日本図や国絵図を実物大で展示し、大きさを体感できるようにしています。

改正地球万国全図

長久保赤水(せきすい)が作成した地図です。

伊能図 中図(中国・四国)

伊能忠敬が作成した地図です。

③都市の時代

近世は、現代につながる都市が作られた「都市の時代」でした。将軍や大名などが政治・経済を集中させるために計画的につくった城下町と、商品流通の発展によって成長した在方町は、共通する社会のしくみや文化をもちました。ここでは、世界でも有数の人口と面積をほこり、日本最大の城下町であった江戸をとりあげます。そして、古文書のほか、ここ20年で大きく進展した近世考古学の成果や、錦絵、古写真、当館が所蔵する日本でも有数の衣裳コレクションなどによって、都市社会のしくみと、都市で花開いた文化を明らかにします。

江戸橋広小路模型

江戸橋から日本橋付近にかけての町並み・市場・盛り場の復元模型です。

女性の衣裳

当時の女性が身につけていた衣裳です。

※定期的に展示替えをおこないます。

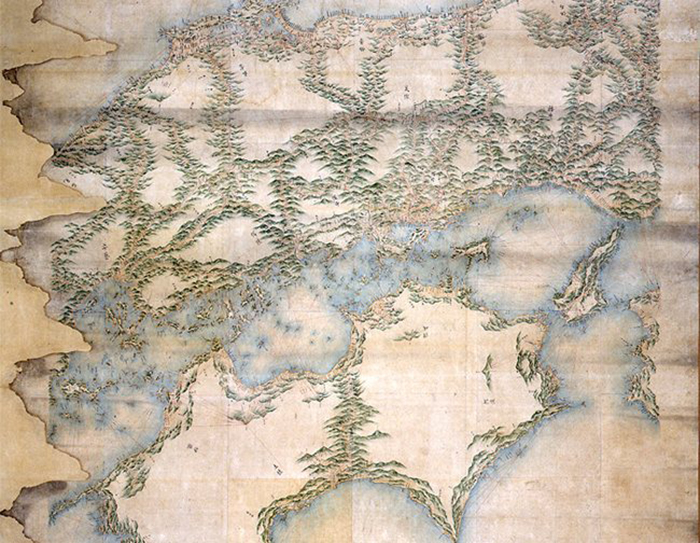

④ひとともののながれ

各地に城下町ができて、多くの人びとが集まるようになると、農産物をはじめさまざまな商品のあらたな流れが生まれるようになりました。とくに、17世紀をつうじて各種の航路や廻船組織が整備され、江戸・大坂間や遠隔地間の船による大量輸送が可能になりました。一方、農業生産力が向上し、人びとの生活が豊かになると、交通路の整備、道中記や道中絵図の出版とあいまって、庶民はいっそう旅へと誘われるようになりました。展示では、旅籠の様子や旅の道具、北前船の活動や紅花の流通などをとりあげます。

北前船と川舟

北前船は北海道と大阪とを結んでいました。(船の縮尺はともに10分の1です)

旅籠「角屋」

伊勢参詣でにぎわった椋本宿の旅籠(はたご)「角屋」の復元模型です。

⑤村からみえる『近代』

18世紀後半以降、村びとは日々の経験にもとづいた技術開発によって生産力を向上させ、くらしにゆとりがうまれると、生活を楽しむようになりました。子どもへの教育も必要とされ、寺子屋の数も都市・農村を問わず増加しました。都市の出版文化も広がり、情報も波及する一方、貧富の差も生まれました。対外的危機感と相まって、政治に対する批判的な考え方や自分たちの地域の文化や歴史を問い直そうという動きが生じ、近代社会の担い手もこのなかから生まれました。展示では、村絵図や農事を描いた屏風などから村の社会や生産活動を読み解いた上で、村芝居などの娯楽、養蚕などの技術、国学・医学などの学問、民衆運動、さらに幕末の欧米の社会の見聞・体験などをとりあげます。

四季農耕図屏風(複製 原品:個人蔵)

農村の風景を描いた屏風です。

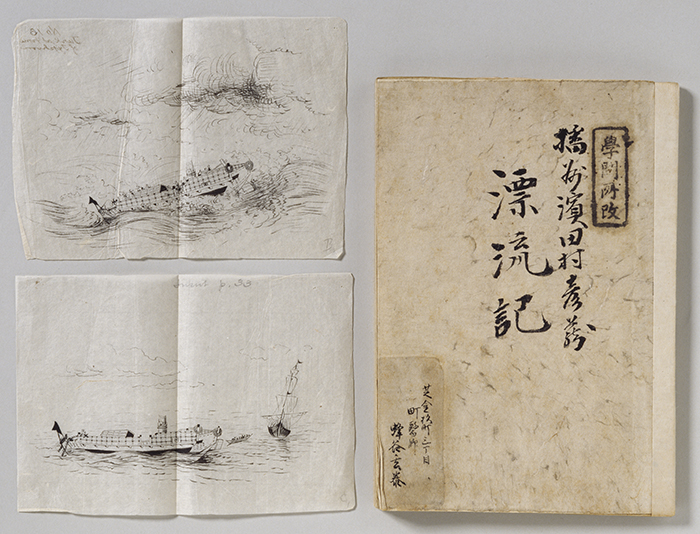

浜田彦蔵『漂流記』草稿

嘉永3(1850)年10月に台風で遭難した浜田彦蔵(1837~97年)が、アメリカ船に救助されたのち、自らの体験を記した記録です。

⑥寺子屋「れきはく」

「寺子屋」の体験コーナーです。江戸時代の手習いを体験してみませんか。ボランティアスタッフもお手伝いします。※開室日時は、日により異なります。

体験風景